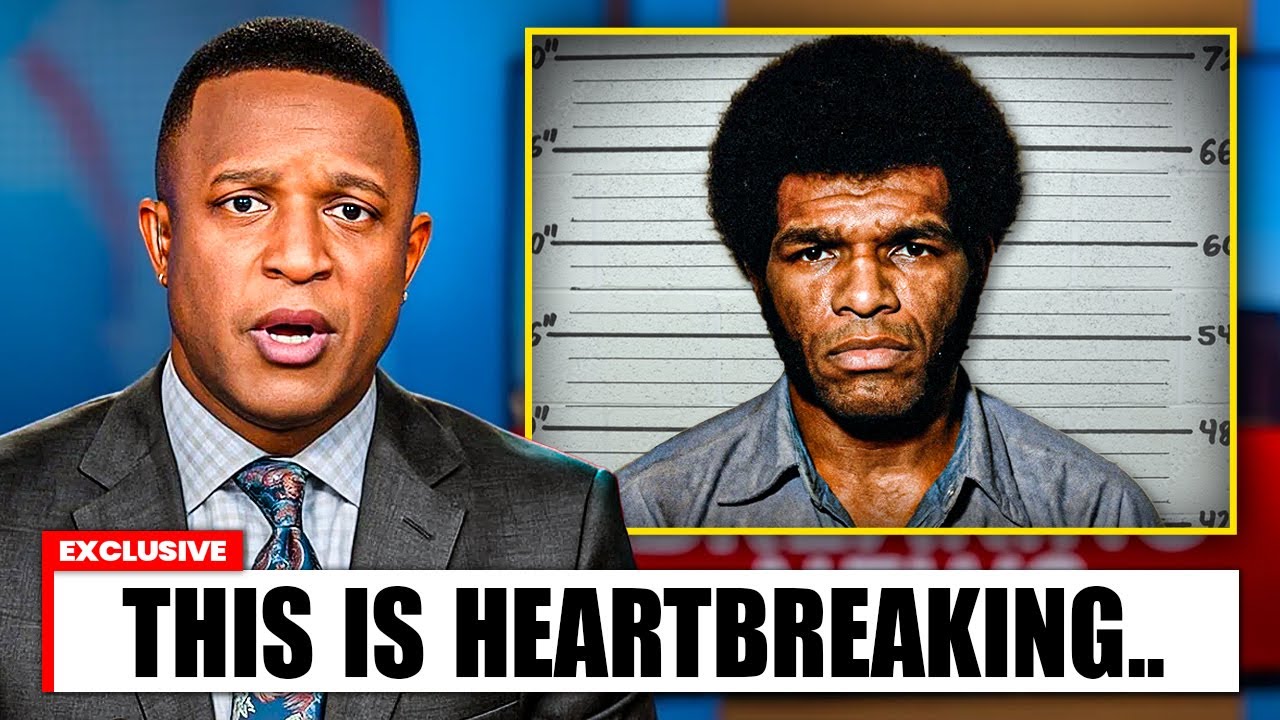

Ron “The Black Dragon” Van Clief: The name evokes an image of unyielding strength, a pioneer who shattered racial barriers in martial arts cinema, and a man whose presence in the fighting world was as formidable as the legend who named him—Bruce Lee.

He was America’s first Black samurai, a five-time world champion, and the oldest fighter ever to step into the UFC octagon. His life, by all accounts, was a blueprint for triumphant resilience.

Yet, behind the golden lights, the roar of the crowd, and the legendary status, Van Clief carried a secret so painful, so terrifying, that he kept it buried for half a century: The raw, blood-soaked memory of a night in the 1960s when he was hanged from a tree by Ku Klux Klan extremists.

This was not a tragedy that occurred far from civilization; it happened while he was serving his country, a young Black soldier training in North Carolina.

The truth, revealed fully only in the twilight of his life, transforms Van Clief’s journey from a story of sporting glory into a harrowing testament to human endurance, a fragment of American history etched deep into one man’s soul.

His survival, his destructive struggle with addiction, and his eventual triumph over the shadows he tried to bury are now resurfacing, painting a portrait of a legend forged not in the dojo, but in hell.

The Shadow of the Noose

To understand the Black Dragon, one must first meet Ron, the 17-year-old Black youth from poverty-stricken 1950s Brooklyn.

Ron joined the U.S. Navy, determined to escape the darkness of his childhood, which included witnessing his World War II veteran father, Larry Van Clief, succumb to a crippling heroin addiction that would eventually take his life. Ron sought structure and a path, but what he found was a nightmare far worse than any street violence.

In the racially-charged atmosphere of 1960s North Carolina, where a Black man holding his head high was seen as an act of defiance, Ron’s dream of serving his country nearly became his grave.

One night, while heading back to the barracks, he was ambushed by a group of white men. They offered no explanation, only cold stares, racial slurs, and the brutal butt of a rifle crashing into his head. He was beaten unconscious, his hands tied, and dumped on a desolate dirt road.

It was there, under the moonlight, that a rope was looped around his neck and he was hoisted from a tree branch—a terrifying ritual of hate carried out by men affiliated with the Ku Klux Klan. The sound of his neck cracking, the agonizing pressure, and then, the silence as everything faded into oblivion—these were the last sensations Ron could recall.

When he awoke, he was in a military hospital, his neck bandaged, his body bruised and broken. Doctors confirmed that he had been clinically dead for several minutes. They could not explain how he was still alive.

For five months, Ron underwent a brutal recovery, having to relearn how to speak, swallow, and even breathe without debilitating pain. But the physical recovery was fleeting compared to the mental wounds.

For years, the cruel laughter of his attackers and the smell of the earth that night haunted his dreams, leading to a severe diagnosis of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and, at his lowest point, contemplation of suicide.

For decades, this horrific event was an unmentionable secret. Though vaguely referenced in his first memoir, the full horror was only revealed in 2020 with the release of the documentary, The Hanged Man.

Ron, nearing 80, finally recounted the moment he thought his life was ending, stating, “I thought I was dead, and God gave me another chance.”

That survival became a profound act of defiance against a system of hate, and martial arts, specifically karate, became his singular lifeline, teaching him the focus and breath control that kept him from the abyss. “If it weren’t for karate, I wouldn’t be here,” he confessed.

The Dragon is Forged in Fire and Chaos

Martial arts was Ron’s salvation. It was a way to channel the anger of his chaotic Brooklyn upbringing and the fear from his near-death experience into a disciplined, focused power. After his discharge, he joined the New York Police Department during one of the city’s most turbulent eras, all while teaching martial arts and working as a nightclub bouncer—sharpening his iron will in real fights for survival.

He quickly became an American phenomenon, winning five world championships in karate and kung fu along with 15 All-American titles, unprecedented for a Black fighter of his generation. Destiny smiled in 1966 when, at an exhibition in Hong Kong, he met the legendary Bruce Lee. After watching Ron perform a precise Goju Ryu Kata, Lee stepped forward and delivered the name that would define him: “You are the Black Dragon.” That moniker was a prophecy, a mark of destiny for a warrior who would transcend racial prejudice.

The Black Dragon flew onto the screen in 1974, starring in The Black Dragon, becoming the first Black action star in Hong Kong cinema. Films like Black Dragon’s Revenge and Way of the Black Dragon captivated Western audiences, carrying the image of a Black martial artist beyond America’s borders. His success was a message: a man once beaten down could rise again through his own strength.

Ron’s influence extended beyond the screen. He founded the Chinese Gojuru karate system, blending Japanese discipline with Chinese fluidity. His philosophy—If the body is a weapon, the mind is its launchpad—was so respected that his martial arts manual became the official hand-to-hand combat guide for the U.S. Secret Service.

The Drug-Fueled Fight and the Memory Eraser

Just as Ron thought he had conquered his demons, a new hell awaited him in mid-1964: Vietnam. Deployed as an artillery commander, he was thrown into the escalating conflict where death was an instant reality. During an ammunition transport mission, the M60 helicopter carrying him was struck by anti-aircraft fire and plunged into the southern forests of Hue. Ron barely survived the devastating crash, suffering severe injuries to his rib, sternum, and spine.

As he lay motionless in the military hospital, his body wrapped in white bandages, a greater tragedy struck: his 22-year-old younger brother, Pete Van Clief, a young paratrooper, was killed after stepping on a landmine. The shock shattered Ron. “That was the day I truly died inside,” he later admitted.

To numb the unspeakable pain and the horrors of war, Ron, whose own father had been an addict, began using painkillers, which gradually led to heroin abuse.

Soldiers called it the “memory eraser,” the only way to sleep without dreaming of blood and death. He hid from nurses to inject secretly, sometimes mixing heroin into his coffee just to survive the searing pain.

The addiction followed him home. In a shocking revelation that stunned the martial arts community, Ron confessed that he once stepped into the ring for the world middleweight championship in 1969 not with just adrenaline, but with LSD running through his veins. He had taken the powerful hallucinogen to escape the relentless pressure and the echoes of war still ringing in his head. In a state of surreal delirium, he fought instinctively, moving with uncanny speed, knocking out his Japanese opponent to be crowned world champion.

Ron refused to be consumed by his dark secret. He kicked his heroin habit the way only a fighter could: through sheer willpower, meditation, and training. Every punch, every kata, he said, was a way to “burn the addiction out of my body.”

His courage to confront his ugliest moments—the lynching, the crash, the heroin, the LSD—made him not less of a legend, but more human, a raw and powerful testament that even the strongest can have moments of weakness, and that survival requires constantly fighting for clarity.

The Final Battle: Silence Over Spectacle

Despite his success, Ron Van Clief never found peace in the spotlight. “I never wanted to be famous,” he stated bluntly. “I made movies just to pay the rent.” The title “The Black Dragon” was the shadow that denied him peace, a spotlight shining directly on the scars he desperately longed to hide.

His personal life reflected this inner chaos: eight marriages and five children, a statistical echo of a soul fractured by relentless trauma. He kept his private life guarded, unable to reconcile the demanding vulnerability of fatherhood with the untouchable persona of a legend.

At 51, when most fighters retire, Ron stepped onto the world’s biggest stage, UFC 4 in 1994, becoming the oldest competitor in history. Though he lost to Brazilian legend Royce Gracie, he left the cage to a standing ovation, hailed as the “immortal warrior.” Yet, this final high point was followed by deep disillusionment. Ron announced his retirement, disappointed in the “commercialized martial arts” that he felt had lost the true spirit of philosophy, turning fighters into products.

Shortly after, the Black Dragon simply vanished. He quietly moved to Hawaii, leaving films, commercials, and events behind, seeking silence. He spent his time teaching martial arts to children and meditating, offering a final, profound wisdom: “I wasn’t born to be a star. Martial arts is meditation. It’s a way of life. Fame is just the echo of others.”

At 80, still practicing yoga and training, even earning his brown belt in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu in 2023, Ron Van Clief remains a living monument to survival. He is a man who learned to live with the two cords that have always defined him: the rope of the past tightening around his neck, and the black belt of discipline saving his soul.

His final victory needs no audience, no medals, and no cinematic titles. It is simply the right to be himself. As he put it, after a lifetime living under the name the world adored, “Now I’m just Ron.” It is the triumph of a man who fell from the sky, nearly died by a rope, and rose from addiction, only to find true strength in humility and silence.

News

The Cycle of Destruction: King Harris’s Jail Trauma, Snitch Tapes, and T.I.’s Lawsuit Against Boosie Shatter the Harris Dynasty

The final, agonizing curtain has fallen on what was once hip-hop’s most formidable and seemingly resilient dynasty. For nearly two…

Secret Flight to Barbados: Unsealed FBI Transcripts Expose a Staged Death and the Untold Tupac Shakur Conspiracy.

The world mourned on September 13, 1996, the day the headlines screamed that Tupac Shakur, the poet, the prophet, the…

The Crushing Weight of the Legend: Lil Meech’s Desperate Leaked Audio Exposes the BMF Empire’s Alleged Financial Ruin.

For decades, the name Meech—specifically, Big Meech of the Black Mafia Family (BMF)—stood as a monolith of untouchable wealth and…

What REALLY Happened to 90s RnB Group Shai.

The Rise, Fall, and Comeback of Shai: A Journey Through R&B History. When we think of iconic R&B groups from…

How Muni Long EXPOSED the Industry and Took Back Her Power.

Muni Long: The Rise of a Controversial Voice in R&B. What if I told you that one of the biggest…

Saucy Santana CLAPS BACK After Nicki Minaj Calls Him a ‘Pig’ on X!

The Tweet That Broke the Internet: Inside Nicki Minaj and Saui Santana’s Explosive Online Feud. In the fast-moving world of…

End of content

No more pages to load